Search the news, stories & people

Personalise the news and

stay in the know

Emergency

Backstory

Newsletters

中文新闻

BERITA BAHASA INDONESIA

TOK PISIN

By Janine Marshman

ABC Classic

Topic:Music

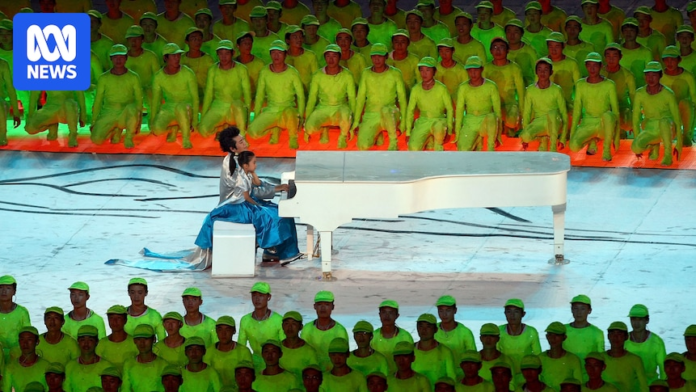

An estimated 2 billion people watched Lang Lang play the piano with five year old Li Muzi during the 2008 Beijing Olympics Opening Ceremony. (Getty Images: Alexander Hassenstein/Bongarts)

Most of us have tried our hands at the piano at some stage. Maybe that's playing Chopsticks with a friend, picking out our favourite song, or more dedicated learning.

The piano features across all western music traditions, from classical music, through jazz and into the popular music we listen to today.

If the internet is to be believed, as many as 40 million people play piano. The data is sketchy, but there's no doubt it's one of the most popular instruments in the world.

And the instrument means a lot to people.

"It's been a powerful emotional and artistic touchpoint for me throughout my life," says ABC presenter Jeremy Fernandez, who started learning the instrument when he was seven.

Australian concert pianist, Tamara-Anna Cislowska started learning when she was about 18 months old and recorded her first music for the ABC when she was just three.

She thinks that people connect so strongly with the instrument because "the piano can read and interpret real emotion."

Voting is now open in the Classic 100: Piano. Tell us your favourites and we'll be counting down Australia's top 100 choices across June 7 and 8 on ABC Classic and the ABC listen app.

ABC Classic is celebrating the piano in its annual poll to find Australia's favourite classical music, the Classic 100.

Every year the network asks Australians to vote for their favourite music in a particular theme, counting down the top 100 across two days. 2025's theme is the piano.

To honour this versatile and beloved instrument, we explore a brief history of the piano in music.

Pianos as we know them today are a relatively recent invention.

Bartolomeo Cristofori invented the piano in Padua in 1700. (Wikimedia Commons)

The piano itself was invented around 1700, evolving into an instrument more like the one we know today in the 1800s. But keyboard instruments, and the music written for them, have been around a lot longer.

Possibly the most famous and beloved by pianists is the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, who was writing for keyboard instruments like the organ, harpsichord and clavichord during the late 1600s and early 1700s.

This music is still inspiring pianists today, such as the now centuries-popular Well-Tempered Clavier collections and the Goldberg Variations.

The musical foundations in Bach's music lay the groundwork for most of the music we enjoy today. You can even find excerpts of Bach's music in songs by The Beatles, Lady Gaga and others.

Cislowska also calls out Domenico Scarlatti, who was composing during a similar period. She credits Scarlatti with demonstrating what the piano might be capable of.

"He did all these innovative things like showing you could repeat notes, or cross over the hands. No-one crossed over the hands before Scarlatti."

Bach primarily wrote his music for God, but it was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart who moved the piano to rockstar status during the last half of the 18th century.

Mozart was a child prodigy. He was considered one of the best keyboard players of the time and played for some of Europe's most famous figures.

During Bach's era, the keyboard was often found supporting other instruments in ensemble or orchestral music. We can thank Mozart for making the piano the star of the show and making the piano concerto so popular.

Mozart's sister Nannerl was also reported to be an exceptional pianist, touring with her brother when they were young. None of her music survived, but there's evidence that she did compose, and some scholars believe she contributed to some of Mozart's music.

While he was just 35 when he died, Mozart wrote 27 piano concertos and swathes of piano sonatas and other music for the keyboard that is still loved today. This includes pieces like his sonata 'Rondo alla Turca', or his variations on the popular French children's song Ah! vous dirai-je, maman. You might recognise this as the tune to Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.

Hot on Mozart's heels was Ludwig van Beethoven, also an incredible keyboard player. His piano music, along with new advances in the instrument, like stronger frames and a bigger sound, stretched the piano to new places.

Some of his music was written for his piano students in the early 19th century, and that music is still a staple for music students today. Almost anyone who's had piano lessons has tried to play Beethoven's Für Elise or the Moonlight Sonata.

But his music could also be explosive and passionate like his later piano sonatas.

Much of Beethoven's later, and more difficult, music was written when he was completely deaf.

As we reach the 19th century, the drama of Beethoven's late piano music unfolds in a new way.

Music becomes freer and more expressive. And more virtuosic, leading to the rise of pianist celebrities.

The reclusive Frédéric Chopin wrote music that still pushes piano technique today and brought a new poetry to the instrument. His music ranged from the introspection lyricism of his Preludes and Nocturnes to the fireworks of Waltzes, Polonaises and Etudes.

Cislowska credits much of Chopin's innovation to his use of the sustain pedal, which lets the notes of the instrument ring for longer.

"He found the soul of the piano because when you use the pedal with the piano and you play it in a certain way you can make it sound more like the human voice," she says.

Around the same time Franz Liszt inspired the term Lisztomania for the fan frenzy at his concerts.

"I think Liszt contributed more to music, and to every aspect of music and performance than probably anyone else has," says Cislowska.

Liszt paved the way for the concert pianist as we know it today, but Cislowska says "he was much more than just a pianist."

His piano transcriptions helped spread music like Beethoven symphonies and Wagner operas to new audiences and he was also a champion for his peers, like Chopin and Clara and Robert Schumann, performing them alongside his own music.

Clara Schumann was a champion of composers like her husband Robert, Liszt and Chopin, playing their music before they were household names. (Getty Images: Hulton Archive)

Around the same time, a young Clara Wiek (who would go on to marry another pianist, Robert Schumann) was a renowned touring pianist. She is credited with popularising the practice of memorising music for concerts.

A respected composer herself, Schumann's music mostly fell into obscurity after her death. Her music is gaining popularity again as contemporary artists champion her work.

Following a little later was the Russian composer Rachmaninov. His music can be daunting for players, comprising of huge stretches of the fingers and a lot of notes.

"A lot of people think it's very virtuosic music. It's not at all. It's just that we're not able to play it because we don't have hands like Rachmaninov…he could play fingering that no-one else could ever play," says Cislowska.

Half a century after Liszt was making audience members swoon with his pianistic pyrotechnics, composers in France were taking the piano in a new direction.

Fernandez couldn't pick a single piano favourite, but "I do love Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel for how dreamy their music is," he says.

Inspired by other artists working around them, like painter Claude Monet, composers like Erik Satie and his friend Debussy focused on conveying mood and atmosphere more symbolically. They also borrowed musical languages from non-western traditions and ragtime.

The music took advantage of modern additions to the piano, like the sostenuto pedal (the middle pedal on most grand pianos that allows only select notes to ring after they're played), to create washes of sound and musical colour.

Leading the charge was the eccentric Satie, who drew on ancient and esoteric influences for music like his beloved Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes.

Debussy's evocative music often used highly descriptive names like "The Sunken Cathedral" and "The Girl with the Flaxen Hair."

Even if you don't think you know anything about classical music you would probably recognise his Clair de lune [Moonlight].

The music has had countless features on screen from that awkward conversation between Edward and Bella in Twilight, to the surreal foot performance by Jamie Lee Curtis in Everything Everywhere All at Once's hot-dog finger universe.

Around the same time in North America, pianists like Scott Joplin were popularising music with African American roots.

The piano was central to the sound of ragtime and is credited as a distinctly American music.

Joplin's Maple Leaf Rag was one of the early hits of published music, with some claiming it was the first piece of instrumental music to sell over a million copies.

Ragtime and the music of Joplin went on to influence early jazz and American composers like George Gershwin.

Gershwin's iconic Rhapsody in Blue bridged the gap between classical and jazz with its luscious melody and jazzy harmony.

You might know it from Disney's Fantasia, or Baz Luhrmann's The Great Gatsby. It also featured in 1984 Summer Olympics in LA, performed by 84 pianists.

The first piano made its way to Australia in 1788, and the instrument has been a firm part of musical life since.

Many composers have looked to the Australian landscape, such as Miriam Hyde's Reflected Reeds, evoking the Sydney Landscape, or much of Peter Sculthorpe's music.

Fernandez says he also sees these influences in the music of pianist Nat Bartsch. "Her compositions are, to me, vivid renderings of the Australian landscape, and a heart full of love and tenderness."

Many composers have brought influences from multicultural experiences, like Uzbekistan-born, Russian, Australian and German trained Elena Kats-Chernin, whose music is flavoured with the multitude of her lived experiences.

Just one example is her Russian Rag for piano, which draws on the ragtime traditions of composers like Joplin, but Kats-Chernin has said it also references Russian café music.

The music of Australia's First Peoples has also been a frequent inspiration for Australian piano music, but in recent years more First Nations artists are telling their own musical stories through the medium of the piano.

In 2020, Four First Nations composers brought their perspectives to 250 years of shared Indigenous and European history in music for a 250-year-old square piano in Ngarra-Burria Piyanna. In the work Rhyan Clapham, Elizabeth Sheppard, Tim Gray and Nardi Simpson each bring a different story to an historic piano akin to the first piano to arrive in Australia in 1788.

The piano has been there since the dawn of the silver screen. Once providing soundtracks live to silent movies, it's still an essential part of scores for film, TV and video games.

The French classic Amélie wouldn't be the same without the joyful, whimsical piano score and Michael Nyman's The Heart Asks Pleasure First has become a repertoire staple.

And the piano is central to Joe Hisaishi's scores for the beloved Studio Ghibli films.

"The piano is very sensitive," he told ABC Classic's Dan Golding in 2020. "It sings the melody line, and the screen world comes alive much more easily."

In the last decade the piano has seen a resurgence in popularity. You're just as likely to see sold-out concerts by pianist-composers like Ludovico Einaudi, Max Richter, Yiruma, and Hania Rani as you are the latest indie-pop sensation.

Einaudi is the most streamed classical artist of all time, ahead of the likes of Bach and Beethoven.

Cislowska thinks that in our "cacophonous world" it's interesting that audiences are gravitating to these pianists who use a lot of repetition in their music.

"When you gravitate towards hearing repetitive sounds it's because it helps you to turn inward. You can go within instead of being forced to be without all the time," she suggests.

Cislowska believes that with the piano "the possibilities are endless.".

There is always so much more piano music to explore. What we often hear and talk about, like in this brief history, barely scratches the surface.

"There's just a handful of composers that we play from and then it's just a handful of their works," she says.

The Classic 100: Piano is your chance to discover some new favourites.

Vote is now open in the Classic 100: Piano. There are over 400 pieces to sample on the voting list, many of which you will hear over the next month on ABC Classic. You can hear what made the top 100 across June 7 and 8 on ABC Classic and the ABC listen app.

Topic:Elections

Analysis by Patricia Karvelas

Topic:Elections

Analysis by Alan Kohler

LIVE

Topic:Explainer

Topic:Explainer

Topic:Music

Topic:Music Education

Australia

Classical Music

History

Music

Topic:Elections

Analysis by Patricia Karvelas

Topic:Elections

Analysis by Alan Kohler

Topic:Australian Federal Elections

Topic:Music

Analysis by Tom Wildie

Analysis by Lucy MacDonald

Topic:Tennis

We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Australians and Traditional Custodians of the lands where we live, learn, and work.

This service may include material from Agence France-Presse (AFP), APTN, Reuters, AAP, CNN and the BBC World Service which is copyright and cannot be reproduced.

AEST = Australian Eastern Standard Time which is 10 hours ahead of GMT (Greenwich Mean Time)

A brief history of the piano in music – Australian Broadcasting Corporation

RELATED ARTICLES