Sections

More from Smithsonian magazine

Our Partners

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine and get a FREE tote.

Lindsay Kusiak

On December 10, 1927, radio host George D. Hay announced the end of an hourlong opera program on Nashville’s WSM radio. Next up was the much more down-home Barn Dance. “For the past hour, we have been listening to the music taken largely from the Grand Opera,” Hay ad-libbed, “but from now on we will present the Grand Ole Opry.”

It was an inadvertent and fateful christening for what would become a cultural institution and eventually the longest-running radio program in the country, introducing tens of millions of listeners to a distinctly American-born genre of music. As Hay playfully commented, the Opry offered a stark contrast to other highbrow programs populating the airwaves, swapping symphonies and arias for jaunty renditions of old Anglo-Celtic, European and African-American ballads played on the fiddle, banjo and guitar. It was hoedown music, or, as Hay lovingly called it, “hillbilly music,” and with a radio boom well underway, Hay had chosen an exceptionally propitious time to share it.

Commercial radio fever swept the nation beginning in 1920, with more than 600 new stations emerging by the time the Opry premiered. But it was not the only barn dance on air, and Hay sought a way to make the show unique. He was known for his theatrical on-air persona, a mordant prude called “the Solemn Old Judge,” and he encouraged each new Opry band to adopt a comical homespun identity that would charm working-class listeners. In the process, he transformed bands like Dr. Humphrey Bate’s Augmented String Orchestra into the

overall-clad Possum Hunters, and other groups into old-timey miners or clumsy farmhands.

As the Great Depression began, Hay’s salt-of-the-earth approach charmed the audience, while WSM made several ingenious business decisions that shaped popular music forever. First, WSM did the unthinkable amid a hemorrhaging economy, investing a quarter of a million dollars—$5.8 million today—to build a new radio tower. It was the tallest in the country and one of only three 50,000-watt clear-channel towers in the United States. It allowed WSM’s broadcast to reach the whole nation. To bolster musicians, whose record sales were plummeting (down from $100 million in 1927 to a meager $6 million in 1932), WSM began sending bands on regional tours during the week, creating one of the country’s first talent agencies, the Artists Service Bureau. Soon, Opry stars were performing for as many as 12,000 people a day at schools or picnics Sunday through Friday, before hustling back to the Opry for their Saturday night radio gig.

In 1939, the Grand Ole Opry joined NBC’s radio network, transmitting the show to 125 stations. It wasn’t long before the Opry’s successes gained a big-time sponsor, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, maker of Camel cigarettes, which sponsored a USO-style tour starring several Opry stars. Called the Grand Ole Opry Camel Caravan, the troupe appeared exclusively for military members at bases throughout the U.S. and Central America during the summer of 1941, charming soldiers with toe-tapping hillbilly music and comedy from Minnie Pearl. A few months later, following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, millions of those same soldiers were now crooning the Opry’s songs on troopships and in overseas barracks as they deployed in World War II.

The show’s new popularity among soldiers spurred the Armed Forces Radio Service (AFRS) to add the Grand Ole Opry to its overseas broadcast in 1943, transmitting the Opry’s weekly show to 306 outlets in 47 countries. By 1945, an AFRS station in Munich reported that Opry superstar Roy Acuff was more popular among its listeners than Frank Sinatra. The show even triumphed in the Pacific Theater, where famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle reported that during the Battle of Okinawa, Japanese troops were chanting, “To hell with Roosevelt, to hell with Babe Ruth, and to hell with Roy Acuff!”

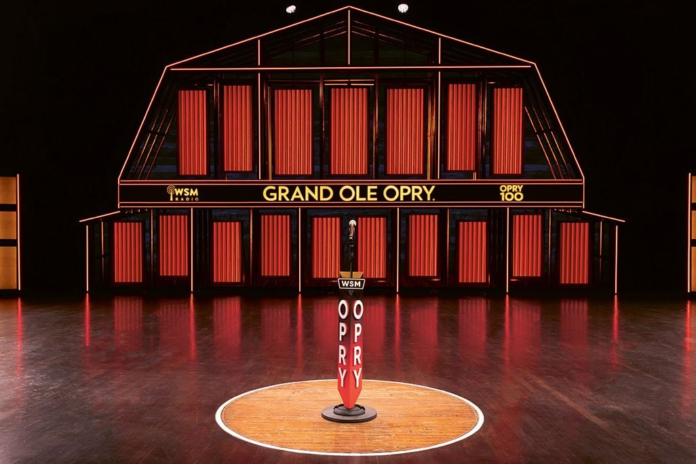

In 1943, the Opry moved into the Ryman Auditorium, the city’s largest venue at the time. And still, the Saturday night showcase—featuring up-and-coming stars like Hank Williams and, later, Patsy Cline, Willie Nelson and Loretta Lynn—sold out each week. It wasn’t until 1974 that the Opry finally moved into its current home, the 4,440-seat Grand Ole Opry House.

Today, the Grand Ole Opry has spent nearly 100 years as a country tastemaker, elevating stars like George Jones, Garth Brooks, Johnny Cash and hundreds more. Thanks to this hardy institution, and contributions by crossover artists like Beyoncé, country music continues to dominate the streaming charts and in 2023 was declared the fastest-growing genre in popular music. As country singer and Opry member Brad Paisley put it, “Pilgrims travel to Jerusalem to see the Holy Land and the foundations of their faith. People go to Washington, D.C. to see the workings of government and the foundation of our country. And fans flock to Nashville to see the foundation of country music, the Grand Ole Opry.”

This article is a selection from the June 2025 issue of Smithsonian magazine

The Opry thrives on a network of stars invited to join its ranks. Here are four of the longest-serving members

By Teddy Brokaw

Bill Monroe — Member for 56 years

It’s often been said that if there were a Mount Rushmore of the Opry, Bill Monroe’s face would be featured. In 1938, the mandolinist formed the Blue Grass Boys, a group so essential in the development of the style that it would ultimately give the genre its name. So popular was the group’s music on the weekly radio program that the show’s manager once told Monroe, “If you ever leave the Opry, you’ll have to fire yourself!” Monroe, who died in 1996, helped launch the careers of other Opry legends like Flatt and Scruggs, and also inspired trailblazers far beyond the country music world: Elvis covered his “Blue Moon of Kentucky”; and Jerry Garcia traveled with Monroe’s tour before forming the Grateful Dead.

Jeannie Seely — Member for 57 years

From the time she was tall enough to reach the dial of the family radio, Jeannie Seely had dreams of the Grand Ole Opry. After a series of hits in her signature “country soul” style, Seely was inducted into the Opry at age 27. She pushed its boundaries from the outset, helping to bring down the “gingham curtain”—the show’s requirement that female performers wear long dresses—by refusing to comply unless the rules were enforced on the audience as well. Seely repaid the Opry with a devotion that persists today, holding the record for appearances with over 5,000. When the Opry House flooded and waters destroyed Seely’s home in 2010, she still performed—in borrowed clothes.

Loretta Lynn — Member for 60 years

For six decades, Loretta Lynn, the “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” constantly propelled the genre forward. Her hardscrabble upbringing in Kentucky, immortalized in her autobiography and its film version (starring Sissy Spacek as Lynn in an Oscar-winning role), seemed to drive her unapologetic approach to music. Hits like “The Pill,” which in 1975 stood as one of the first songs to tackle the use of birth control, nearly caused her to be banned from the Opry. A defiant Lynn played “The Pill” three times during one Opry show and told media, “If they hadn’t let me sing the song, I’d have told them to shove the Grand Ole Opry!” Lynn died in 2022.

Bill Anderson — Member for 63 years

| Read More

Lindsay Kusiak is a Los Angeles-based culture and entertainment journalist.

Email Powered by Salesforce Marketing Cloud (Privacy Notice / Terms & Conditions)

Follow Us

Explore

Subscription

Newsletters

About

Our Partners

© 2025 Smithsonian Magazine Privacy Statement Cookie Policy Terms of Use Advertising Notice Your Privacy Rights Cookie Settings